Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS

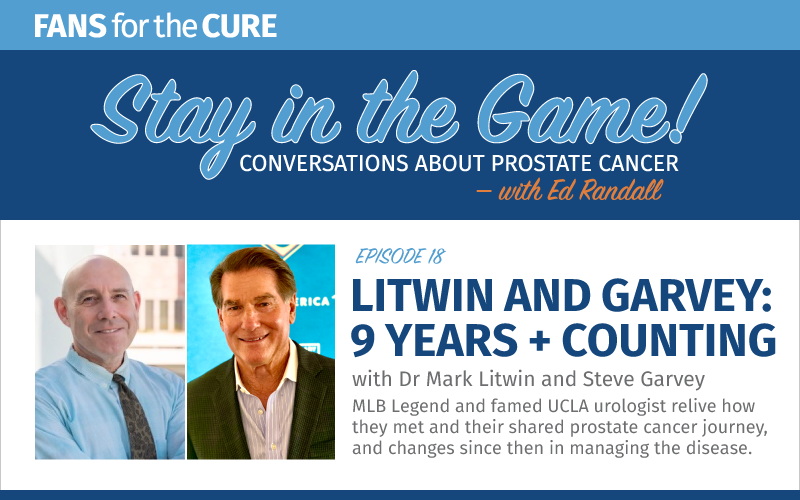

MLB Legend, Steve Garvey, and famed UCLA urologist, Dr. Mark Litwin, recently caught up to relive how they met, revisit their shared prostate cancer journey, and discuss changes since then in managing the disease.

Mark Litwin, MD, MPH, is chair of the Department of Urology, a practicing urologic oncologist, and professor of urology, health policy & management, and nursing at UCLA. Dr. Litwin is a translational population scientist who teaches and conducts research in quality of care, health-related quality of life, medical outcomes, medical decision-making, costs and resource utilization, patient preferences, and health care access.

Program Notes

- Dr. Mark Litwin on the UCLA Health website

- VIDEO: 2021 Sherman Mellincoff Faculty Award: Mark Litwin, MD, MPH

The Stay in the Game podcast is sponsored by Cancer Health – online at cancerhealth.com.

Cancer Health empowers people living with prostate cancer and other cancers to actively manage and advocate for their care and improve their overall health. Launched in 2017, cancerhealth.com provides accessible information about treatment and quality of life for people with cancer and their loved ones, along with information about cancer prevention and health policy.

Episode Transcript

Welcome to Stay in the Game: Conversations about prostate Cancer with Ed Randall. Here we’ll chat with doctors, researchers, medical professionals, survivors, and others to share and connect. This show was produced and shared by Fans for the Cure, a non-profit dedicated to serving men on their journeys through prostate cancer.

Steve Garvey: Hi, this is Steve Garvey and I’m chairman of the board for Fans for the Cure. It’s my pleasure to be the guest host for Stay in the Game, a podcast for the National Prostate Cancer Awareness Month.

And who better to have as my special guest for Prostate Cancer Awareness Month than urologist, who I think is quite simply an oncologist who saved my life about nine years ago? He is chair at UCLA Urology as well as a translational scientist who teaches in the schools of medicine and public health at UCLA. And is simply my pleasure to introduce Dr. Mark Litwin. Mark, thanks for joining us.

Dr. Mark Litwin: Hey. It’s great to be here.

Steve Garvey: Well, who would have thought nine years ago when Candace and I walked into your office that all these things have happened over that, almost a decade now, in terms of our relationship, in terms of the things that you and I have been able to work together on, and of course, the advancement in the fight against prostate cancer. But let’s go back to that first day when Candace and I walked in.

And as we know, the women in our lives or our significant others are the ones in this case usually drive us literally and figuratively to get questions answered about something that could be life-threatening. And I think Candace asked the first nine questions. Am I correct?

Dr. Mark Litwin: I remember it well. She asked the first nine and the last nine, as I recall.

Steve Garvey: Well, I asked one. She let me ask one. And I’ll never forget this. I looked at you… and you know, you have such a wonderful demeanor. And I looked at you and I said, “What would you do?” And you looked at me and it was as if I was looking at a Hall of Fame pitcher and you said, “You know, Steve, I’m 55, 52.” I’m taking five years out of it. “But you know, I’m at the top of my game. Let’s take it out.” And that was enough for me, and I’m quite sure it was enough for Candace at the time.

And I just want to thank you for, not only be listening to both of us, which I think is so very important but that you stepped right up and gave me the answer I was looking for. And it could have been anything else. But I think it’s so important in a patient-doctor relationship for that to be so straightforward and honest.

Dr. Mark Litwin: Well, I think you’re right. The interaction between patient and doctor I believe really is as critical as the skill set of the doctor him or herself. I remember growing up as a kid on the East Coast in South Carolina watching you play baseball and really admiring you as kind of a childhood sports role model. And the honor to be able to be in a role many years later to help you and to, you know, as you said, extend your life has been a combination of an honor and a blessing really for me.

But I do remember that day very well when you and Candace came to the office, diagnosis of prostate cancer having recently been made. And there was fear. And it is very humbling to see grown men, particularly people who have been at the top of their own games really scared, really, really scared at an existential level. And yet to be able to enter a situation like that as a physician, and know with great confidence that I’m going to be able to help, that’s a special honor to be able to do that.

Steve Garvey: And again and who would have thought from moment to standing on the mound at Dodger Stadium where I had a chance to thank you by putting you in front of 50,000 people throw out the first pitch. I mean, really? And then you stepped up and threw… I’m pretty sure it was a swing-and-miss strike. How did you feel about that?

Dr. Mark Litwin: I have the ball in my office in a little Lucite container that you kindly signed for me afterwards. And I’m pleased to tell you there is no dirt on the ball. And it went, fortunately, by the grace of God, or whatever, from my hand into the catcher’s mitt of the fellow that caught it. That was at least as stressful for me as walking into the operating room to do a difficult operation. Because normally I don’t have 50,000 people watching.

Steve Garvey: Yeah, that’s what I was going to ask you. You know, you walk in, you see me there, you open me up, and then there’s my prostate. So that’s easy, right? I mean, that’s a straight fastball. Of course, what you did after that is not so easy, but I was so proud of you.

And of course, ever since then, we’ve had a chance to go to Dodger Stadium from time to time, and we always will. And to share that moment but to share the national pastime baseball. I think it’s great. Thank you for mentioning how young you were as a little boy watching me play. I mean, thank you so much.

Dr. Mark Litwin: Not a little boy, but just an adolescent. Let’s say adolescent.

Steve Garvey: A little adolescent then. Let’s touch on some important points now. Bring us up to date on what aspects of diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer have changed over these last nine years since I was a patient?

Dr. Mark Litwin: Well, I’ll tell you a lot has changed in the diagnosis and management of guys with prostate cancer. Probably one of the most exciting things has been the advent of MRI scans to help diagnose prostate cancer.

When you were coming through all of this about 10 years or so ago, we had ultrasound and ultrasound was pretty good at imaging the prostate, but nowhere near the precision of what an MRI scan can do. And that really has revolutionized in the last 10 years, the diagnosis of prostate cancer.

So the precision with which an MRI scan can identify not only a tumor deep within the prostate but also the extent of that tumor, whether it is contained within the prostate or whether it appears to be spreading beyond the prostate into the structures that are nearby it just has advanced our ability to get a really good handle on the extent of tumor very, very early on in the process.

So we use MRI today as really the gold standard in guiding prostate biopsies. Like any medical test, it’s not 100% accurate. Nothing, of course, is, but it’s much better than straight out ultrasound used to be. So that is one of the most significant advances over the last 10 or so years is the use of MRI to diagnose prostate cancer.

Steve Garvey: Yeah, thank you. You know, we also talk about the PSA. I think more than anything else the PSA has been batted back and forth over the years. Tell us about the PSA. Tell us about the beginning of it, the evolution, and where it is now in terms of diagnosis.

Dr. Mark Litwin: Sure, very important question. And it gets to an area in medicine and public health that we call epidemiology. And over the last 18 months or so, a lot of people have learned a lot about epidemiology because of viral epidemiology with COVID-19. But the epidemiology applies to things like PSA testing as well.

PSA, as you know, stands for prostate-specific antigen (PSA). It’s a blood test. It’s a protein that occurs in the blood that’s very easy to measure. It was popularized in the late 80s, early 90s. And what we saw when PSA came on the scene is a huge spike in the diagnosis of prostate cancer.

And it’s very interesting epidemiology phenomenon. Because in retrospect, we don’t believe that there was actually increase in the number of cases that existed. But with the advent of PSA, there was for sure an increase in the number of cases that we diagnosed.

So it’s really important because that spike in diagnosis really put prostate cancer front and center for a lot of men. It attracted a lot of attention in the media, in the world of entertainment, in the various sports worlds, and really throughout the country and throughout the world.

And as time has gone on over the last 30 years or so since PSA came on the scene, we’ve learned a lot about it. And one of the most important things we’ve learned is that PSA is very good at identifying patients who might have a prostate cancer. Again, it’s not 100% accurate.

But what it’s not so good at is identifying which men have prostate cancer that needs to be treated. And this is one of the key advances in our knowledge, our understanding of prostate cancer over the last 10 or 20 years even now, which is that not all prostate cancers that are diagnosed actually need to be treated. And so that plays into another major advance over the last several years, which is the use of what we call active surveillance, or non-treatment for men who have a low-grade, low-risk prostate cancer.

So prostate cancer come at different levels of risk. There are high-risk tumors, and there are medium, and then low-risk tumors. And for many years, we treated all of them the same.

But what we know now is that the super low-risk tumors don’t really provide much of a threat to a patient’s life or even his quality of life. So those we separate out in general don’t treat those guys. Whereas those who have a higher risk tumor, we do treat. So PSA helps us sort through all that.

And there have been additions to the PSA. So just the straight out PSA blood test is now embellished with additional versions of the molecule that allow us to look very, very precisely at what components of PSA might be elevated. And that helps us also in determining not only who has prostate cancer, but who has a high grade prostate cancer. Because those are the ones we really want to capture.

Steve Garvey: Well, Mark, we’ve covered the PSA. Tell me about DRE. And in talking to men, talking to them about this, tell me a little bit about it.

Dr. Mark Litwin: DRE stands for Digital Rectal Examination. I’ll tell you as an aside, it is not uncommon that patients come in thinking it’s some kind of computerized thing because of the word “digital.” But let me just clarify that the Digital Rectal Examination, the D, the digit that’s referring to is the finger. The doctor’s digit. Doctor inserts a gloved finger with a little bit of lubricant into the rectum to palpate or examine the prostate gland.

Now, understandably, this is not the thing that most men look forward to when they go to a doctor. And my advice to them, in general, is get over it because it can save your life. It’s not that bad. As simple as that. Get over it, lean over, have the exam.

And that in combination with the PSA is very, very effective in making a diagnosis of prostate cancer. And the reason is that if there’s a tumor growing in the prostate, the doctor can feel it directly by putting a finger on it. And that’s valuable information that people get.

Steve Garvey: Well, it’s probably one of the top three topics in men’s jokes, don’t you think?

Dr. Mark Litwin: Absolutely. And Steve, you can try me, but I guarantee you I’ve heard them all.

Steve Garvey: I bet you have. Well, in one example, especially for our listeners, we’ve done a number of screenings at stadiums and arenas around the country. If you were to say what does Fans for the Cure do, we’re an awareness foundation. But we’re really in over 120, 130 stadiums and arenas every year.

We did a screening at San Diego Petco few years ago, and we had the opportunity to do a DRE and or just to take a blood test. And if you took the blood test, you’d get an 8 by 10 picture. But if you did the DRE, then you get an autographed ball. Well, it made men think. But we went from, I think, our usual 30 or 40 to close to 80 or 90. So it was quite a testimony to me. But it does show that for the right piece of memorabilia, you can bribe men to do anything.

Dr. Mark Litwin: Everyone has his price.

Steve Garvey: Let’s talk about us in general—men—and what they perceive to be about prostate cancer and what the realities can be. And the need, maybe is importantly as anything we talk about, the need to engage men and the realization that this is dangerous, the single most important men’s killer per se. And they need to listen and they need to learn, and they need to talk about it.

Dr. Mark Litwin: You’re right. It’s the most important cancer for men to consider. It is, as I was saying before, a cancer that comes in two basic overall types or flavors. There’s the kind that doesn’t kill you. That as you mentioned earlier, men are more likely to die with than to die of. That’s the one you want if you’re going to have this. And then there are the more aggressive forms that absolutely can lead to death from prostate cancer.

I think that many men, many of us kind of put our head in the sand when it comes to health care. We feel invincible. We are often in control at some level of our worlds and our work and in other aspects of our lives, in our leisure activities, etc., driving the boat, swinging the bat. You know, that is a role that many men are accustomed to.

And when you introduce the idea of a cancer, or any condition really, medical condition, it takes us out of control. And that’s scary. And that’s legitimately really scary for a lot of people. I think this is why, as you were saying before, many times it’s the significant other, or the spouse, or the partner that is really pushing the medical diagnosis and the medical treatment.

But what I would say to that having treated many, many men over many, many years for prostate and other types of cancer is that you allow yourself to remain in control and to remain armed if you arm yourself with information. And I’m quite sure that when you were playing ball you knew all your stats at all times. Probably in real-time with every inning, how it changed.

And so I would say that the same thing is of value when it comes to PSA. Know your stats. Your PSA is an important statistic that you should know in order to make decisions about your life and about your health.

Now, it’s really critical to point the following thing out. Many of the organizations that issue guidelines based on evidence and science about whether men should or shouldn’t get a PSA test done have issued guidelines that say for many men it’s not worth it to even get a PSA. And that can be confusing to people, particularly if you’re hearing messaging that cuts the other way like you’re hearing right now.

The interesting thing is that that guideline, that guidance is based on the fact that for many years, once a PSA was measured, if it were elevated, that automatically lead to a biopsy. And if a cancer were present, a treatment. And many of those treatments ended up being unnecessary.

And so because of that, the entities that issue these guidelines, say, “Hold on a second, Jack, let’s just not get PSAs at all.” And many of us who practice evidence-based medicine, although we understand that recommendation, disagree with it.

And my perspective on it, as a professor of both urology and public health at a top university here at UCLA, is that you should get the PSA drawn, but what you shouldn’t do is necessarily go on to treatment even if you get a prostate cancer diagnosed.

And this gets back to the other issue that we’re talking about, which is that some prostate cancers need to be treated, so you really want to know about those, and others don’t need to be treated. So know your stats, know your diagnosis, and then you decide if treatment is right for you or not.

And as you mentioned before, many men who are diagnosed with prostate cancer are at an age where there are other medical issues going on as well. Men in their mid, late 70s, 80s, etc., have other issues: cardiac issues, pulmonary, liver issues, various diseases that we all accumulate with age. And if those are really the big gorilla in the room, then prostate cancer gets back-burnered.

Whereas if an individual like you, Steve, when you were diagnosed is younger, healthier, fit, has taken care of himself and can look forward to 10, 20, 30 years of life ahead, well, then you really ought to have a conversation about whether that prostate cancer should or shouldn’t be treated.

But my perspective on it is know the information and then sit down and have a thoughtful, reasoned, shared decision-making conversation with a doctor who you can connect with and really communicate with.

Steve Garvey: Let’s stay on this for one more moment. How often should the PSA be taken? Number one. And at what age should it be started? Number two.

Dr. Mark Litwin: Groups that issue guidelines in favor of PSA testing say that the PSA ought to be measured starting at age 50 and it should go until about age 70. Some group say 75. And it should be done either annually or every other year. And that the start time for getting PSAs should be moved earlier to age 40 if an individual man has a father or brother with a history of prostate cancer—that is a first-degree relative because we know there’s a genetic element—and or if the individual is of African ancestry.

So black men in this country are known to have higher rates of prostate cancer and higher death rates from prostate cancer. We don’t understand the biology of that completely. And there’s probably many factors that go into it.

Part of it may be molecular and very biological. Part of it may be the social construct of race in our society and how that impacts whether men are able to get health care and how well they’re able to access it. But however you want to unpack it, black race, whatever that means, is known to be a risk factor for prostate cancer. And so for them starting at age 40.

And then we stopped prostate cancer testing around age 70 or 75. Why? Because at that age, other diseases begin to kick in. So as I often say to my medical students and residents, in a 75-year-old man with prostate cancer, the most common cause of death is not prostate cancer. It’s dropping down of a heart attack.

And so if there’s an elevated PSA, and a diagnosis of prostate cancer in a 75-year-old, and the man is 25 pounds overweight and hasn’t been out of the easy chair in two years, other than to go to the fridge, you know, he’s got some other work to do.

Steve Garvey: And we really haven’t had improvement in the numbers for black men, have we?

Dr. Mark Litwin: The overall rates of prostate cancer death have gone down over the last 30 years. In 1992, the rate of death of prostate cancer was about 40 men per 100,000 in the population. Currently it’s about half that. And so the rates of death have gone down.

But black men die at higher rates per population than non-black men. And again, we don’t completely understand all of the reasons for that, but it’s enough of a marker that one should be aware of that when making decisions.

Steve Garvey: Let’s go to real-time. Let’s talk about obviously the evolution from 2020 to 2021 with COVID. Looks like a serious decline in cancer screenings with the general population over that time. It’s got to be concerning with men like yourself and women also in the medical profession.

Dr. Mark Litwin: Well, it is. This has been one of the great fears that many of us in healthcare have is that because COVID so completely overwhelmed so much of our health care system over the last year and a half, routine care for things like cancer screenings, cardiac issues, diabetes screening, you know, all the other medical diseases that aren’t COVID have suffered. They really have suffered.

I think that as the statistics get published, you’re going to see increases in rates of advanced prostate cancers and other cancers being diagnosed because people weren’t going in to be tested. And it’s understandable. People were afraid to go into a hospital where they perceive there was a lot of COVID. And then there’s less than 100% uptake on the vaccines as everyone knows.

And so this is going to be with us for a while most people think. And people have to recognize that COVID is not the only disease people can get. We have to pay attention to the rest of our health as well.

Steve Garvey: And when we talk about health in general, let’s talk a little bit about are there ways of helping to prevent prostate cancer with diet, exercise, maybe some of the things you know about in terms of preventative actions?

Dr. Mark Litwin: So this is a question that is very, very common among men who I see. Not those who have prostate cancer already, but those who are coming in for routine screening. They get good news, the PSA is fine, the DRE didn’t show anything. And then the next question is, Well, what can I do to prevent prostate cancer?

And the short answer is that the data are less than overwhelming but they are at least circumstantial. That attention to diet and exercise can effectively decrease the risk or prevent prostate cancer. And so the dietary alteration is to eat a diet that’s low in fat and high in fiber. So more roughage and less fat and fried foods, less red meat.

To eat a diet that has extra soy products in it. Soy includes things like tofu and related products. And also a diet that is high in what’s called lycopene. Lycopene is a component of the diet that is often found in red vegetables and fruits. Tomatoes, in particular, cooked tomatoes, in particular, as well as guava, and certain other fruits and vegetables. So those that are high in lycopene are also thought to be helpful. So that’s diet.

And then exercise. A lot of good studies have shown that regular exercise, which is of course good for many other reasons other than prostate, is also helpful in preventing prostate cancer and even in limiting its growth once it’s diagnosed.

Steve Garvey: We always talk about a team. And you’ve told Candace and I we’re a team. That the family is a team and addressing this. Not just Steve Garvey had prostate cancer, the whole family was dealing with prostate cancer. So what would you say is a good team process of dealing with it once you get the diagnosis?

Dr. Mark Litwin: Well, I agree with you. It’s about having a good team and having a good coach, to continue with that metaphor. Prostate cancer is very common. And there are many, many doctors and providers available to people, but this is a time to really consider what’s the quality, what’s the skill set of the physician that you’re dealing with.

And so in general, those doctors who are at a major center have better quality, both in terms of the counseling that they provide, but also in terms of the skills of the actual procedures or treatments that they’re doing.

And so whether it’s a surgery, like you had, to remove the prostate, and whether that’s done through an incision, or whether it’s done more commonly nowadays through a robotic approach with what’s called laparoscopy with tiny little incisions, or whether it’s radiation therapy that’s being delivered—and there are many different types of radiation that can be used in prostate cancer—or whether it’s one of the newer treatments, such as a high fru, which is high frequency ultrasound to ablate the prostate or destroy the prostate, whether it’s cryotherapy, which is freezing of the prostate, whether it’s the use of lasers. Any of the new technology that I can’t even think of off the cuff right now.

You want to be in a center that’s got a good reputation, that’s going to provide high quality because there is variation in the quality of care from one doctor to the next to the next. And so basically the advice is get to the best possible care you can get you. This is a time to really pull out the plugs and ask for recommendations, regardless of where you are to get to the best person.

Steve Garvey: We also have faced this situation where the desperation of the significant other and not being able to convince the potential patient to be proactive. And not only do you have to be a medicine man, so to speak, but you also have to be a psychologist and a psychiatrist, I’m quite sure.

Dr. Mark Litwin: What I would say is regarding cancer screenings in particular is that these are often decisions that people make with their emotional brain, you know, the lizard brain, and not so much with the thinking cognitive brain. But whichever one you have to activate, get tested so you’re armed with the information.

Again, know your statistics. Know how you manage the information and what you do with the information, you know, is open for discussion. But just at least know the numbers, know the statistics so you can get with a highly qualified doctor and make a decision about, first of all, does it need to be treated? Or are you fortunate enough to have one of the good cancers that can be safely observed? Or is this a situation where you say, “Wow, I sure am glad I went in because this life of mine could have gone one of two ways, and I’m able to control it back to the the trajectory that I want.”

Steve Garvey: Men will always say… probably one of the first two questions is how will it affect my sex life? And I think that’s is greatest fear as death sometimes with men before they start thinking it through.

Dr. Mark Litwin: This is another reason to get to a top quality provider, whether it’s a urologist or the radiation oncologist or a medical oncologist, so that treatment, if it’s necessary, can be given in a way that maintains sexual function.

The risk comes because of the anatomy of the prostate. Literally the geography of the prostate. The prostate gland is deep inside the pelvis, as most people know. It can have an impact on urination, which is why men as we get older have more difficulty emptying the bladder. Every 12-year-old kid knows that when you go to the restroom at Dodger Stadium you want to stand behind the 20-year-old guy in front of you and not behind the 70-year-old guy who’s in front of you, so that you’re going to get out of the bathroom faster.

So the prostate impacts urinary function. But it also is located very close to the sexual function nerves. The nerves that actually go on down to the penis that are responsible for creating erection are located immediately adjacent to the prostate gland. And because of that any treatment of the prostate, surgery or radiation, or otherwise, can have an effect on those nerves.

But the great news in all of this is that we have a very, very nuanced understanding of the anatomy today and we have excellent techniques to avoid injuring those nerves. It’s not always possible but in most cases it is possible to avoid injuring those nerves so that men can resume their own levels of sexual function that they had prior to treatment.

There is an important factor here to consider. The average age of diagnosis of prostate cancer is 67 years. And what I can tell you is that a 67-year-old man’s erection is not the same as a 27-year-old man’s erection. And so the reserves are already less in that age. The bench is not as deep in that age group. And so we work hard to preserve and maintain whatever the baseline function is that the man brings. But one has to be cognizant of the fact that at 67, or 72, or 74, or whatever age, there may already be some impairment, if you will, in sexual function.

But the other good news is we have treatment for that, too. So even absent the discussion of prostate cancer, a good urologist has treatment for that as well. So it’s 2021 going on 2022, there has never been a better time in human history to have a diagnosis of prostate cancer than right now.

Steve Garvey: Nitric oxide, is that beneficial?

Dr. Mark Litwin: That’s exactly right. So nitric oxide is the name of the neurotransmitter, the chemical that is released from one nerve ending to another in the penis that stimulates the blood vessels to swell up and cause erection. And the erectile nerves that can be damaged during prostate cancer treatment are responsible for making that nitric oxide.

And the medications that we have today are very, very powerful at increasing the levels of nitric oxide so that erection can be enhanced and be resumed. And even in the absence of nitric oxide, there are other ways that we treat this issue if it becomes an issue. That’s a whole other podcast. But there are great treatments available both to preserve erectile function and to help return it if it is impaired afterwards.

Steve Garvey: I am now making you head of the fansforthecure.org advertising pro bono staff because, yeah, I’ve got my clients involved in the bathroom advertising. And everybody laughs but it really is effective. So I think Fans for the Cure should have a sign “if you really have to go, stand behind a younger guy.”

Dr. Mark Litwin: Exactly right. If you really have to go, stand behind the young person not behind the old guy with a big prostate.

Steve Garvey: So where are we going in the next 5 to 10 years?

Dr. Mark Litwin: Well, if I take out my crystal ball by the next 5 or 10 years, my view is that what we are learning about prostate cancer more and more is that because we are doing such a good job of imaging the prostate, visualizing the tumor within the gland, the next big thing in prostate cancer treatment is something called focal therapy.

Focal therapy refers to treating not the whole gland, but one focus of cancer in the gland, hence the word focal therapy. This is now approved by the FDA. And there are more and more studies being done on what’s the best form of energy to deliver to the prostate to that focus of cancer to knock out the cancer without ablating or knocking out the whole prostate and the nearby structures. So focal therapy is one of the next big things that is really already here. But I think you’re going to see more and more about it over the next 5 to 10 years.

The other next big thing, which is not even a year old is something called PSMA scanning. PSMA. It sounds like PSA, but it’s different. PSMA it’s a type of a PET scan. It was developed at UCLA as well as several other places, and it was FDA approved at the end of 2020. And insurance companies are working through the particulars of trying to get it covered now.

But it is an exquisitely sensitive form of a scan that can detect metastasis or spread of the prostate cancer anywhere in the body. And it does so much, much more accurately than the standard tools and forms of scans that we have been using for 30, 40 years.

And so if the prostate cancer is in the high-grade group, the high-risk group that we were talking about before, it is particularly important to be able to find out has the cancer spread anywhere, such as to a lymph node to a bone, or some other part of the body, or is it contained?

Because if it’s contained within the prostate, then it’s treatable much more effectively than if it has spread. Even if it spread, we have really terrific treatments, but it’s a different kind of a discussion if it has spread. And it’s very, very helpful information to have. Again, it gets back to the theme of knowing the information. Know your stats, know your information.

So this PSMA PET scan is something that I believe you’ll be seeing more and more coverage of over the next 5 or 10 years.

Steve Garvey: Mark, I’m going to embarrass you a little bit now. You know my relationship with UCLA health is extensive, from having my left hip replaced in 98 and then the prostatectomy eight years ago and being on the neurosurgery board.

But UCLA health has won significant award and that’s the Mellinkoff Award that you were given in 2021. And it’s an outstanding award for excellence in the field of medicine at UCLA. And it goes beyond just that. And I want to make sure I tell everybody about that, how significant it is, and how blessed we are to have you as an advisor for us and a disciple. And so from all of us to all of you, congratulations again.

Dr. Mark Litwin: You caught me off guard. I didn’t know you were going to ask me about that. I would tell you at the outset I’m embarrassed to talk about it. But it’s the equivalent to the many MVP awards that you won in your ball-playing career.

Dr. Mellinkoff was a much-beloved dean of the medical school here at UCLA. He passed away not long ago. And the faculty here in the medical school created an award in his name, the Sherman Mellinkoff Award to honor the faculty member in our medical school who follows the ideals that Dr. Mellinkoff pursued, which is both science and humanism and compassion in medicine. And it is generally viewed as the highest honor that can be bestowed by the medical school faculty at UCLA. And I was incredibly, incredibly humbled, and honored to receive that award earlier this year in 2021.

Steve Garvey: Well, Dr. Litwin, this has been quite an adventure in this series for Fans for the Cure.

Dr. Mark Litwin: Thank you, Steve. It’s an honor and a pleasure and a blessing to be involved.

Steve Garvey: God bless you, my friend. And to all those listening, we hope you’ve enjoyed this episode, and we hope you’ll continue to follow us and hear more about prostate cancer from those who made a significant difference in the battle against it. Have a good day and thanks for joining us.

Thanks for listening to the show. You can find program notes and a full transcript at the charity’s website, fansforthecure.org. Be sure to subscribe to our podcast in iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher, and everywhere good podcasts are available. And if you like what you heard, a positive review on iTunes will help other people also find our show.