Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS

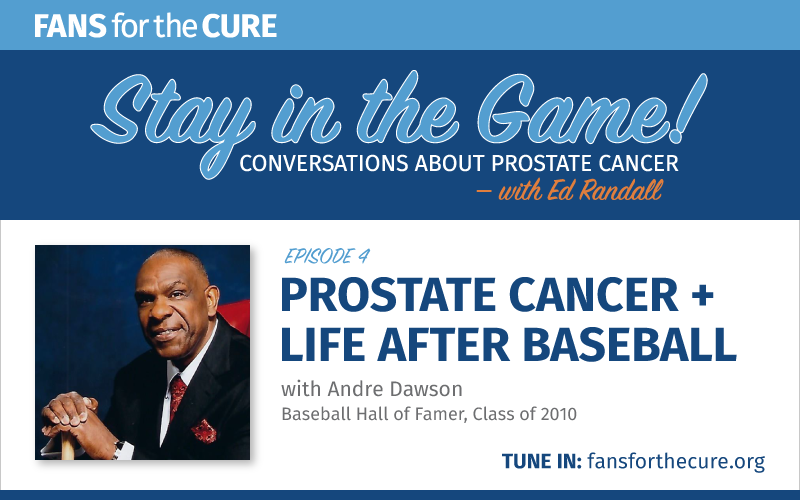

Baseball Hall of Famer Andre Dawson talks about playing Major League baseball, his own journey with prostate cancer, and serving his local community as the owner of a funeral home.

Program Notes

Episode Transcript

Welcome to Stay in the Game: Conversations about prostate Cancer with Ed Randall. Here we’ll chat with doctors, researchers, medical professionals, survivors, and others to share and connect. This show was produced and shared by Fans for the Cure, a non-profit dedicated to serving men on their journeys through prostate cancer.

***

Ed: I can’t think of another funeral director who’s in the Hall of Fame, the Baseball Hall of Fame. This is after overcoming 14 knee surgeries and 2 knee replacements to become only the third player in baseball history to hit 400 home runs and steal 300 bases, make 8 All Star teams, win an MVP award, and was runner up twice.

It’s a great pleasure and honor for me, Ed Randall, the founder and CEO of Fans for the Cure, that my special guests on the fourth episode of the Fans for the Cure Stay in the Game Podcast is Baseball Hall of Famer and so much more than that, Andre Dawson. Baseball is a game of numbers, so here are the ones that landed him in Cooperstown. He put up 49 home runs, 137 RBI, and an MVP Award in his first season with the Chicago Cubs the first time in the history of the award that voters gave the honor to a representative of a last place team.

Andre, we’re so honored to have you. Thank you so much for taking the time to be with us and support Fans for the Cure yet again.

Andre: Thank you, Ed. It’s my pleasure.

Ed: Now, if I’m you, and God forbid, that was the case, Andre, I would look up on baseballreference.com a minimum of five times today just to make sure that I was still in the Hall of Fame. When you last looked up yourself and your career, what are the numbers that impressed you the most?

Andre: Well, you know, I wasn’t really a numbers guy. What was more important to me was longevity. And I felt that through longevity, everything at the end would kind of even itself out. So the most important thing for me was playing 20 years when I was told that I would be lucky if I play four. Because that was the average career lifespan of a big leaguer.

In all honesty, I almost walked away from the game during year four because of a fracture in the kneecap and on the knee itself. The pain was so excruciating, I had to take Darvocet as a form of medication. Just to get through a game I had to take three. And that was a lot within about a five, six-hour period just to get through the game. The end result when the game was over, the pain would return. And I can remember sitting down telling my wife, “I can’t do this. I can’t go out. One Darvocet, the first one makes me a little bit woozy and lightheaded and I can’t go out and play under those circumstances.”

She convinced me to just go to management and sit down, have a conversation, and let them know the problem I was experiencing. And sure enough, that’s the direction I went. And they panicked. They really didn’t know what to do. They discussed, gave me some time off. The sad thing about it was it was over a month into the season before they actually decided to take x rays. I was experiencing this discomfort as well back in spring training.

When they did take the X rays and they showed the fracture, they just decided as opposed to put me on the disabled list, they would cut my playing time. Throughout the course of the year, the fracture started to heal itself and I was gradually starting to come around. But that was something that literally almost forced me to walk away from the game. So I look back, I knew with all of the issues I had with the knee injuries, the knee problems during the course of my career, longevity was something that I had to focus on a little bit more, I had to make our work ethic a little bit more, and packable off the field.

In regards to determining what my future was going to be, I just knew that this could be something that could end at any time. So I had to be more aware of what I was doing, where I was at on the playing field. As I said, I ended up playing 20 years. I would have never thought. So when you think about the numbers, all of that stuff was just an accumulation of being able to go out there and put 20 years behind me, and at the end walk away from the game and give the uniform back as opposed to have taken away.

Ed: But something you said that I want to jump on, why did it take so long for you to get that exam? Why did it take a month? Why didn’t they do your wishes right away?

Andre: Ed, that’s the million-dollar question. I got cortisone shots, I had fluid drained and the pain was just there. It was there for the entirety of the offseason. One thing I didn’t mention is I did have surgery right at the end of the season. It was just one of those things in the offseason. I went through my physical therapy, my rehab, but the pain would never subside. It carried on into spring training. I don’t really know. I don’t know why it took so long for them to take the X rays and stuff. But that just got to be pretty much old news for me when it came to spring training and having to go through that type of ordeal.

I would always have a fluid accumulation at some point doing spring training because of the workload. Then I’d have to get a shot of cortisone, which would have to be repeated in about four weeks because the fluid itself would come back. And then I would be good to go for about most of the first half up into the All-Star game.

Ed: When we look back on the Montreal Expos, they gave us, the fans three Hall of Fame players: you, Gary Carter, Tim Raines. You’re moving along in your career with tremendous knee pain through the 1986 season, crazy things are happening in the front offices in baseball with something called collusion, and your contract is up after the 1986 season in Montreal. Tell us how you wind up with the Chicago Cubs for the 1987 season and the great story about how your salary was determined.

Andre: Well, I was coming up on my free agency here. We did sit down and try to discuss going forward what was going to be pretty much my fit with the organization. I didn’t really want to become a free agent even though I knew that gave me leverage. I wanted to wear one uniform the entirety of my career, but I realized after 10 years that the damage had already been done, and it probably would be best for me to move on if I could get on a natural playing surface.

But we did sit down myself, Dick Moss, who was my agent at the time, and the owner, Charles Bronfman, the very last day of the season. Bronfman said that he was optimistic that things will get worked out but the general managers had a different perspective. They felt that they could assign me and it could be on their terms for less money. But I just felt that that was a slap in the face what they were offering. This kind of extended on into the offseason. At that point, I met with John McHale, who said their offer was still on the table. They were offering me a $200,000 cut in pay…

Ed: Wow

Andre: …to resign as a free agent. I honestly said to John, “I don’t think that this is going to be viable. And if this means that you don’t have to go ahead and test the free agent market, that’s where I was going to focus my thinking.” And that was the last that I heard from them. We went into the offseason. There were no feelers. There was nothing pretty much. No offers from anyone. Dick and I sat down and we had a conversation. I met him out in California at his home and we devised a game plan to test the market with the understanding that there probably won’t be a lot offered from other ballclubs.

But I looked at it in a sense that, “Okay, this is where we are at this time. If a team makes me an offer, and it’s not overly embarrassing, then you know, I swallow my pride and I’ll accept it.” And I had made the determination that I wasn’t going to go back and play in Montreal under no circumstances. I just felt that they didn’t really extend to me a sincere effort in the offseason to resign me. Though their writing is pretty much was on the wall.

So Dick and I said, “We’ll go out. We can’t really make a monetary offer.” There were two teams in mind. We were going after Arizona with the cabs. Number one on the list was Atlanta. Atlanta because it was closer to my home. But the Cubs is where I want it to to be. It was still within the division. It was a natural playing surface. I’d always had better numbers in daytime baseball. They had a following and a huge following around the country itself. They had GN, a superstation, and I just felt that that would really be a unique opportunity if it presented itself.

So we unexpectedly met with Dallas.

Ed: Dallas Green, right?

Andre: Dallas Green, correct. Spring training actually had already started. We gave Dallas the proposal. I said, “Here’s a blank proposal. I’m not going to come and sit and talk to you about monetary issues. Just pay me what you think I’m worth, and I’ll sign the contract.” Dallas didn’t really know what to make of it. Initially, he said, “What is this? I said, “You know…”

Ed: He thought it was a trick.

Andre: Yeah. He said, “I have young players that I need to give an opportunity to make this ballclub and make the starting lineup.” And said, “Well, I see, that’s all well and good. But you still have pretty much intact the nucleus of the team that went to the playoffs as far back as three years ago.” I said, “I feel that I can be a perfect fit for you.” He said, “Okay. I need my legal people to look this over. Can I get back to you in a day?” I said, “That’s fine.” I said, “I’m going to leave it on the table for 24 hours and I’m going to West Palm Beach and I’m going to talk to the Braves. I’m going to give them the same opportunity because that’s a little bit closer to my home.”

And sure enough, the next day, I get a telephone call from Dallas, and he said he said, “Sir, son, the best offer that we could make you is $500,000.” That was $500,000 less than what Montreal was offering. I knew where he was going with it. It was a ploy to persuade me to move on because you weren’t really supposed to be negotiating with free agents. It was pretty much it out for him. But I accept it because I say, “Mr. Green, that’s fine. I will. I’ll accept your offer.”

He got quiet for about 15 seconds and I thought I lost him.

Ed: He hung up.

Andre: I said, “Hello,” and he said, “I’m here.” He said, “I’m here.” He said, “Can I call you back in about an hour?” I said, “Sure. I will wait for your telephone call.” Sure enough, he called me back and he said, “Welcome on board. We’re glad to have you.” I know you were just here yesterday, take your time and get back out.” I said, “It won’t take me long. I’ll be back out tomorrow.” That’s pretty much sums it up how I became a Chicago cub.

Ed: Wow. What an incredible story. On your bronze plaque at the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, you’re wearing a Montreal Expos cap. Given that there were six glorious years in Chicago, was the expos cap a difficult decision?

Andre: Well, it wasn’t my decision. I was told right after the announcement that we would sit down and we would discuss what emblem I would wear on the hat. And my preference of choice was to go in as a Chicago club. I felt that kind of rejuvenated me. Even though it was only six years—I played 10 years in Montreal—Chicago is what catapulted me probably to that status. I had some wonderful years in Montreal, but I love Montreal and the real bit of terms. I was dissed by management. When I became a free agent, they said my better years were behind me and that they offered me what they did because of their concern with my knee history.

Well, I just felt that, again, that was another slap in the face. So I didn’t have a lot of good feelings as a result of going ahead and being a free agent. And there were other things that surfaced and came to life about my playing days there. But I just felt that that fan base embraced me. It was a love affair from day one. Andres Army was created out in right field. I mean, from day one of my putting that uniform on I just felt the sense of relief and a welcomed attitude.

Like I said, it was only six years but it was six wonderful years. It was probably the best and exciting time during my playing career. I remember having this conversation with friends and family and I said, “I think this is the way I want to go. I want to always be remembered for my time in Chicago, more so than in Montreal. Yes, Montreal gave me my start, and I appreciated that. I gave them the 10 best years that I could under the circumstances, but…

Ed: And you had a lot of happy memories up there?

Andre: Yes, I did. I met some wonderful people, teammates, fans, and it was an exciting plan across the board. It was a different type of sense of feel for the game itself as opposed to being in the States. But Chicago was just so special. It was the love affair, the fans around the country who you would encounter when you were on road trips. Like I said, it was just so different of a feel for going out and playing the game itself. Again, that’s just how if I went into the Hall of Fame I want is to wear the cab emblem on my cap.

Ed: Switching gears. You and I are among over 2 million men living among us who are fortunate to have survived our journeys with prostate cancer. How did you come to be diagnosed?

Andre: Well, it’s funny. Every spring training before you step out on the playing field itself, you have to take a physical. That’s management, that’s players, everybody associated with own field activities. For me, it was pretty much routine. I had done it all the course of my career. I can bashfully remember sitting in my locker and having a doctor have the trainer summon me into his office.

And he said, “Well, your physical, everything checked out, pretty fine.” I’ve always been fairly healthy even post-career. He said, “But there’s one thing that concerns me.” He said, “Your bloodwork has come back with your PSA numbers elevated.” And he said, “There’s no sense of urgency says but I probably would like for you to see a urologist at some time.” I didn’t really think anything of it.

Ed: Yeah, of course.

Andre: You know, because it was spring training. I just took it upon myself, “Okay, once the season is over, then I’ll go see a doctor and see what was going on. I still feel perfectly fine.” I was having no problems. Then I did go see the doctor, and we did some additional blood work. About a week later, he set up a meeting. He called me in and he said, “Mr. Dawson, I have bad news.” And I could see the look on his face.

When he said bad news, the one thing that really didn’t come to mind for me was prostate cancer. I said, “Well, I want to know what the bad news is.” The first thing he said to me, he said, “How are you feeling?” I said, “I’m feeling fine, doc.” I said, “Go on. Let me have it.” He said, “I think you have prostate cancer. I want to make sure because I want to do a biopsy.” I elected to go ahead. “I want to do it as soon and as quickly as possible.”

We did the biopsy and sure enough from the samplings he took, there were about four parts of it that came back and it tested positive. He looked at me and said, “We can pursue this a number of ways.” And I said, “Doc, I just want to rid myself of it as quickly as possible. Just let me know what I need to do.” He said, “We can try to chemo-radiation.” I said, “No, you’re talking cancer, I wanted out of my body as quickly as possible.”

He said, “There’s a procedure, robotic surgery that we can move forward with.” He said, “Let me ask you another thing. How is your sex life?” I said, “It’s fine as well as I know.” He said, “Okay, there could be some complications.” I said, “But we’ll try to be as minimally invasive as possible.” He said, “But I just want you to know.” He said, “It’s your call, whatever you want to do, I’m here for you.” “That’s the direction we want to go.” I said, “Doc, I just want to have the surgery as quick as possible because I wanted it out of my body.”

Ed: It was shortly after your diagnosis and your operation, and you and I were in touch, that I was on my tour of spring training camps in Arizona and in Florida. And I had completed the Arizona portion and now I’m in Florida, and the Miami Marlins for whom you’re working with at the time are sharing a complex with the St. Louis Cardinals. Ed is asked to speak to the St. Louis Cardinals organization early in the morning. Then I am accompanied by one of the assistant firm directors of the Miami Marlins to the Miami side.

I saw you in uniform and you called me over, and that summoning led to one of the most dramatic moments in the charity’s history. You said to me after we hugged, you said, “I want to talk after you talk. They don’t know. There’s 150 or so Florida, Miami Marlins minor leaguers assembled along with staff, coaches, managers, trainers, strengthen conditioning coaches,” and you said, “today’s the day they’re going to find out.” I spoke. I hardly spoke to confine my remarks, and I introduced you. And you told them what happened. I will never forget that.

Andre: Yeah. Just standing there listening to you, I was a brush that you were coming into camp and you will make it around, and you were going to be speaking. I wanted to listen in and hear your message. And believe it or not, after hearing you speak, I felt touched emotionally. You probably weren’t aware; I had tears in my eyes. I said to myself, I said, “God, this is the moment.” I said, “This is something I need to share. There are not a lot of people that know that I’ve gone through the battle with cancer itself.” I can’t really call it a battle because post-surgery I had some minor issues that were addressed and I kind of got my pain tolerance down.

But I just said, “Just give me the strength to go up and to be able to stand up to these young men and kind of finish up what Ed had started and left off, and let them know that there’s a victim among you. And why I feel that as you’ve already heard, as is necessary importance on why you probably should be aware of issues that are going to combat you and affect you. If not now, maybe later on in life. I just feel touched after hearing you. That gave me a sense of confidence to just go ahead and step forward and be able to talk to and reach out to these young ballplayers. I got such an emotional lift after being able to get that off my chest.

As you mentioned, no one was really aware of that. But it just took you coming down and doing what it was you did, coming in, and giving them a broader scope of the disease itself, how it affects men and what we were basically going to be faced with down the road. Like I said, after I was done, I was able to address the media and talk to the media about it. And like I said, I just felt a huge, huge sigh of relief afterwards.

Ed: Thank you for the kind words. Like COVID-19, the diagnosis and the mortality rates for prostate cancer in the black community are two and a half times those of whites and Asian men. Blacks are chronically underserved by the healthcare industry, but they also compound it by not going to the doctor. How do we, you, Andre Dawson, me, Fans for the Cure start to convince black men of the importance, Andre of going to the doctor?

Andre: They really don’t buy into the seriousness of prostate cancer itself until they’re inflicted with it or someone that they know or someone close to them is inflicted with it, and know what the dire consequences are. They think that for the most part, they’re safe. And they hear stories about, well, you shouldn’t seriously consider it until you reach a certain age, and then how you can live on. I do know this: that some people can probably live with it and die with it. And it may not be the thing that kills them, but it can cause other prolonged issues.

I just took a sense and a feel for “Hey, the sooner you know about this, the earlier you know about it, the earlier you will go and get detected, and you will able to nip this thing in the bud, the better chances are living a longer life and living without it. It can’t be cured.” The way you reach people is I think the way we do it now. They either accept it and adhere to what it is we’re trying to instill and let them know, hey, this is what you’re up against at some point in your life. If you can’t be receptive of this, that’s the only thing we can do. We could be the platform for them to just take the seriousness of the thing and do something about it. It’s always it’s your life is at stake.

Ed: Now, you have entered into another life. You’ve joined basically the family business, which you did some time ago, but now it’s become public. You have been a mortician in your native Miami for 12 years. And God knows, Andre, you’ve been challenged more than ever during this once in a lifetime—please God let it be once in a lifetime—COVID-19 pandemic. If you would, as a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame class of 2010, how surprised are people when you tell them what you do for a living today?

Andre: Well, they’re not really surprised anymore. I think the cat is out of the bag. But initially, I had a lot of fun with it because of the looks that I would see on their face. Most of it was along the lines of “you’re doing what?”

Ed: You’re doing what? Yeah.

Andre: I just had to break it down to them. I said, “Well, yeah, this is where I am at this particular point in time.” And I have to get them to understand, “Well, I’m not really the embalmer per se. I’m the owner of the funeral home. I have a staff. I have a life as a director. I see a lot, and I’m educated a lot about the business itself now, but there are certain things that I do with that, I don’t do.” I say, “But I am the owner of a funeral home. This is kind of where God has placed me. I would have never thought and this is a conversation I had with my staff. Who would ever have thought?” I say, “But you know what, if this is where I’m supposed to be at this particular point in time in my life, then I know that this is probably a calling so I have to just put my best foot forward and make the most of it.

Ed: And you’re so humble, you did not put your name on the funeral home.

Andre: I didn’t want it to be about me. Like I said, I told my staff, “This is not about Andre Dawson. It’s not about you. When you come through those two double doors, there’s a job to be performed. And that is catering to families who are in one of the worst times of their life. For me, baseball instilled in me quality and professionalism.” I told them that’s who I want. That’s the kind of personnel that I want.

The fact that I was able to assemble the staff that consisted of individuals that have sort of a background, I think the funeral home business is an extension of the church itself they have a religious background, that made the process going forward a little bit easier also. But I didn’t want this to be about Andre Dawson. It was about a service that the community required and needed. And I just wanted to make sure that I was able to accommodate them in that manner.

Ed: I can’t imagine what this crisis has done to your life in your business and turned everything upside down. Describe what has been different about helping people deal with loss under these tragic circumstances.

Andre: Well, it’s tough. Initially, it was tough to get people to buy into services are going to have to be conducted a little bit different now because of the protocol when it comes to the pandemic itself. When people grieve, when they mourn, when they want to put away a loved one, they have a sense of wanting to be together. It’s difficult under the circumstances to get them to buy into “we got to separate to you.”

For me, I had to acknowledge the fact that the pandemic has caused a lot of havoc in so many ways. When it comes to social distancing, for instance, we have to make sure that they are aware that we can accommodate them in a manner that is conducive to their safety, to the safety of the staff, and to the safety of all parties involved. So what we had to do was limit how we conduct our services when it came to how many people can actually attend services themselves, especially if it involved the chapel service at the funeral homes.

The churches kind of opened up a little bit. That’s initially only allowing 10 people, 15 people, later on did 20 and 40. Now, even with proper social distancing, a few more. But the families, the toughest part is, of course, they’re grieving, they’re mourning, but they can’t grieve properly. Families like to gather in masses when it comes to a send-off. And that’s something we had to really, really do a stellar job to get them to understand that, “Hey, your safety is of the utmost importance. This is critical and this is how the pandemic has caused things and matters to be where they are.”

Ed: They are death certificates to be signed, bodies to be picked up, families to console, loved ones to be buried. And you had to learn when the appropriate time is to sit and listen, and when you have to be a counselor because everybody grieves and mourns differently. Many of us have lost relatives, friends, and loved ones to this insidious disease. Part of what you do is offer comfort to people at a time of this unspeakable sadness. What do you say to them?

Andre: Well, you want to listen, more so than be a voice. Because for the most part, they want to be heard. And you let them grieve. We had a lot of crying when families come in to make arrangements. A lot of them feel a lot of guilt in a sense for whatever reason. But we just try to hear them out. You don’t want to say a whole lot, but you want to remind them that you’re there for them. You can’t say anything, you can’t be the individual that say, “I feel your pain.” That’s not the appropriate thing to say. You just make them aware that, “Hey, we’ll keep you in prayer. This, among other things, too, shall pass.”

You just got to get them to understand that the grieving process for many has its place and it’s difficult to get over with initially. It may take some people a lot longer than others. Some people never get over the process. But you got to make them aware that you’re always available for your stance with them or the things that you try to convey with them doesn’t stop after their loved one is placed in the ground itself. But you’re always there to comfort them, and to help them through the process.

Ed: I get the sense that this has humbled us so much. If you would, talk about how you have handled this emotionally.

Andre: Well, it’s tough. Like I said, I would have never thought that this would be my calling, in a sense. I looked at it, I didn’t think it was going to be as tough a challenge as it turned out to be initially. But once I got both feet in and I just felt comfortable with “this is where I am, this is what I’m doing,” I accepted it. I had to get my family to buy into it, my kids. There were some unpleasantries. Initially, I really didn’t know what to anticipate of it. I can recall my son looking at my daughter doing the grand opening and made a comment, “What are they doing?”

Now both are involved. My son a little bit more involved, because he’s kind of the day to day operations now. But I for me, I had to accept it for what it is. And knowing that I was bringing a viable resource or keep it a viable resource in the community. So enable to extend and give the families a helping hand, that just made it so much easier for me. Now that I look back, it’s been – what? 12 years now. I’ve welcomed it with open arms.

The toughest thing though is people that you know, babies, kids, teenagers, those are the toughest services. But I just say to myself, “I can see a lot of emotion when I’m attending services, and I’ll always distance myself to watch the back of the service itself because I reflect a lot. And I just think about the sadness that service brought me when it came to one of my loved ones. That’s how I tried to isolate myself from what’s going on.

But I had to let it grow on me, which it eventually did. Like I said, once I was able to grasp it full force, I just thank God and say, “This is where you placed me and I thank you for how you have guided me through all the process over these years.”

Ed: Your quote is “All I want to do at this point is to be able to continue to serve. I believe I’m right where I belong.” Last thing before you go. What is your Hall of Fame message to men, especially to black men, with regard to being aware of and educated about what you and I have gone through—prostate cancer?

Andre: Get tested. Get tested for your loved ones. This is your life, but it’s not about you per se. As much as I took a lot of pride and effort in taking care of my body thinking that this is going to be something that I’m going to have to do all of my life because I want to be healthy all my life, prostate cancers is something that’s inevitable. You’re going to get it at some point. It might be late. It might be early. But the earlier you do it, as soon as it’s diagnosed, the better your chances are of surviving and living a healthy and healthy life thereafter.

So it can be inflicted into someone who puts health above everything else in his life. And it definitely can find you. But I just say, just get tested. Get tested as early as possible and stay on top of your health. Stay on top of the testing. Just know that if you are inflicted that there are means and measures that can be taken and that can lead you to live a normal and healthy life.

Ed: What an honor it is to spend time with you, Andre. Bless you. Bless the family. Please stay safe. Stay well. Thank you so much for being with us.

Andre: Ed, my friend, it’s always a pleasure. You stay safe. God bless you.

Ed: And we thank all of you for watching our Fans for the Cure Stay in the Game Podcast. I’m Ed Randall.

***

Thanks for listening to the show. You can find program notes and a full transcript at the charity’s website, fansforthecure.org. Be sure to subscribe to our podcast in iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher, and everywhere good podcasts are available. And if you like what you heard, a positive review on iTunes will help other people also find our show.